I saw something today for which I have been looking for many years. When my Y-DNA test some years ago confirmed the widely held theory (in our little part of the world) that the Littles of Ashe County, North Carolina descended from the indentured servant Abraham Little (1671-1720), I began to search for historical records related to my indentured servant immigrant ancestor whose surname I carry. Even though there still exists a break in the paper-chain of genealogical records around 1800 (the father of Isaac Little (1800-1884) remains unconfirmed–for now), the genetic relationship between the Littles of Ashe County, NC and Abraham Little (1671-1720) who arrived in Virginia in the mid-1680s is convincingly strong, such that regardless of who his father turns out to be, Y-DNA testing confidently suggest that Isaac Little (1800-1884) is a grandson or great-grandson of Abraham Little (1671-1720). So to approach the mystery of Isaac’s paternity from another angle, now that DNA testing had suggested whose Isaac’s ancestors were, I have been doing extensive descendancy research on Abraham Little (1671-1720).

At least as far back as 2002, the late Leo Little (1950-2008), a pioneering genetic genealogist (and who was my sixth cousin with whom I share the most recent common ancestor and Y-DNA descendancy of the aforementioned Abraham Little) speculated that the Littles of Ashe County, NC were descendants of Abraham Little (1671-1720). (Please take a moment to read the touching memorial of Leo Little written by one of today’s leading genetic genealogists, Blaine Bettinger; similarly, Roberta Estes, creator of DNA-Explained.com, and another of today’s leading genetic genealogists, also paid tribute to Leo Little.)

In his extensive collection of records relating to Abraham Little (1671-1720), Leo Little (1950-2008) included this golden nugget; posting to the Geocities-hosted(!!!) website LittleGenWeb, Leo Little wrote, “Virginia: Stafford County: 1692: Abraham Little shall be freed from his indenture to Abraham Beckington as of 15 Nov.” But, as was common at that time at online genealogical forums, no citation for the information was given.

Desiring to firm-up the claims attributed to Abraham Little and his descendants, I began to look for the documents that lead earlier researchers to note these events; that is, I began to create proper source citations for as many historical claims as I could. I keep two family trees: one that is “in pencil,” speculative and contains working theories, but another “in ink,” in which every claim is thoroughly documented with source citations. Many of the sources were easily found given the extensive records available online at Ancestry and FamilySearch.

But an important claim remained unconfirmed: the allusion by Leo Little and others that Abraham Little had been released from his indenture in 1692. Repeated, countless online searches failed to lead me to a specific, accurate citation pointing to an actual historical document. And searches for the original historical documents were also fruitless. I never found anything more specific than ‘Stafford Orders 1692.’ And many of Stafford’s records were no longer in the county, as other counties had later been created from the original large county. And later, Stafford would become one of many “burnt counties” of the South whose records were lost during the Civil War. So I would return to the search again and again, then set it aside for weeks and months at a time, only to return later to try to find the actual order freeing Abraham Little.

This week, when I noticed that a speaker at a genealogical conference I was attending was an expert on colonial Virginia court records, I decided to ask for a search strategy that might lead me to the elusive 17th-century court order. Giving a talk titled “Getting the Most Out of Virginia’s Court Records” at the Virginia Genealogical Society 2021 Virtual Conference, Victor Dunn was the right person to ask for help; a full-time professional researcher who specializes in Virginia research, Dunn has served in leadership at state and national genealogical organizations, and, especially helpful for me, he serves as coordinator of the Virginia research track at a prestigious institute for professional genealogists.

Anticipating that there would be a question and answer session at the end of his presentation, I prepared a question to post to the virtual host to relay to Dunn. Here is the question that I pasted into the chat window:

Mr. Dunn: I need help verifying a claim about a 17th century court record. In 2009, a researcher posted some information to a Stafford County, Virginia genealogy forum about brick walls. The researcher posted this claim:

“I started with Abraham Little in which a 1692 Court Record read: ‘Abraham Little shall be freed from his indenture to Abraham Beckington as of 15 November.’ Any help with this family would be appreciated.”

Since 2009, many Little family histories have alluded to this 1692 court record, but without proper citation. I have been unable to find and confirm this 1692 court record (online searches of Stafford order books being fruitless), though Y-DNA tests at 111 markers confidently suggests that I and several dozen Little/Lyttle/Lyddle men across the U.S. share this indentured servant immigrant ancestor. Could you sketch out a search strategy to find this 1692 court record, so that I could properly cite it, locate the physical book, and photograph the order?

Unfortunately, the host, perhaps thinking the question was too long and not having the time to fairly paraphrase the question, asked Dunn instead a question that bore little resemblance to mine. Not, however, wanting to squander this opportunity to ask an expert for advice, I dashed-off an email to Mr. Dunn, thanking him for his informative talk, and explaining that I had tried to ask for a search strategy during the question and answer session. In my email, I included the original question that I shared with the conference host and as shown above. And I clicked Send.

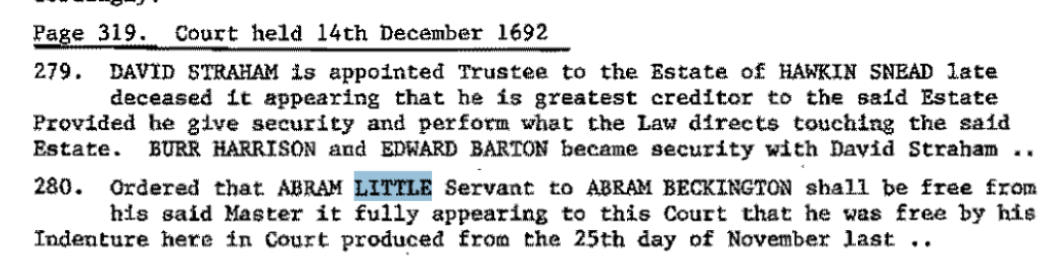

Ordered: That ABRAM LITTLE, Servant to ABRAM BECKINGTON, shall be free from his said Master, it fully appearing to this Court that he was free by his Indenture here in Court produced from the 25th day of November last.

Court held 14th December 1692, Order 280, Stafford County Order Book, 1689-93, page 319.

About three hours later, I received back a reply that far surpassed my expectations, soaring beyond my hopes of the inquiry. Mr Dunn wrote:

I found the following in Ruth & Sam Sparacio’s Stafford County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1692-1693 (McLean, VA: Antient Press, 1988) p. 61. It seems very likely that Abram Little was an indentured servant.

Wow! This was exactly the citation for which I had been searching for years. And not only did Mr. Dunn find and send to me the prized citation, there was more. Included with the email was an embedded snippet of a screen capture, evidently a search of the Sparacios’ Stafford County, Virginia Order Book Abstracts, 1692-1693, apparently a PDF or online version:

And that wasn’t the last or even the best gift that Mr. Dunn shared that day. Far beyond offering suggestions on how I might search for the lost citation, Mr. Dunn had not only sent me the citation, but he had included a screenshot of the abstract, and further, he sent one final, additional blessing. Mr. Dunn also sent to me information about where he believes the Sparacios had found the order book from which to create their abstract.

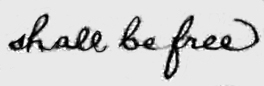

Following that lead, within moments I was seeing for the first time online microfilm images of the original manuscript order book, including this order liberating Abraham Little from his indentured servitude: “Abram Little, Servant to Abram Beckington, shall be free.”

Stafford County Order Book 1689-93, page 319; Stafford County Microfilm, reel 7, image 217 (Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia)

The whole order, about only 40 words, entered on page 319 of the order book recording court business on Sunday, December 14, 1692, reads: “LITTLE v BECKINGTON: Ordered: That ABRAM LITTLE, Servant to ABRAM BECKINGTON, shall be free from his said Master, it fully appearing to this Court that he was free by his Indenture here in Court produced from the 25th day of November last” (Stafford County Order Book 1689-93, page 319; Stafford County Microfilm, reel 7, image 217; Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia). The order is shown here:

Stafford County Order Book 1689-93, page 319; Stafford County Microfilm, reel 7, image 217 (Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia)

The whole page on which the Abraham Little order appears in the order book is shown here:

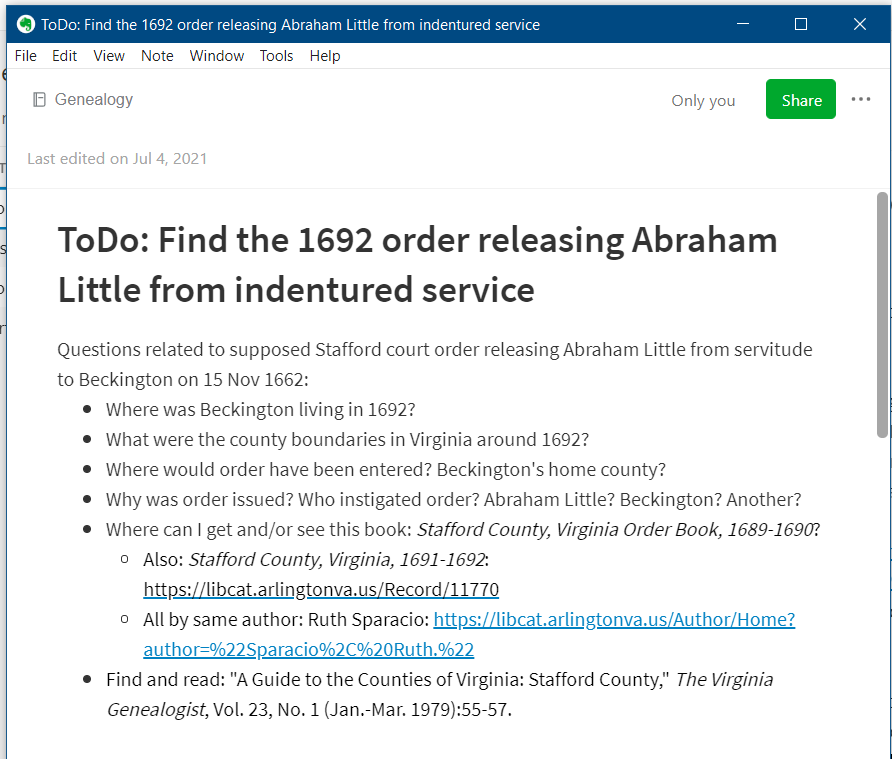

Looking back over my research logs to see how close I might have come to finding the record myself, I just now noticed that on July 4, 2021, I had identified the author of the abstract, Ruth Sparacio, almost had the title of the abstract correct, and had identified a library holding the abstract. This is a screenshot of my Evernote genealogy research log from that day:

Close, but no cigar. I don’t know if I wouldn’t have eventually found the record–I’d like to think that I would have–but I can’t calculate how long it might have taken me, especially since the abstracts are not online at the major genealogical sites, and that the microfilm has not been indexed.

Two or three take-away lessons come from this episode, this blessing: One: the record you are looking for is likely not the low-hanging fruit that is quickly found at Ancestry, MyHeritage, or FamilySearch, but that just makes the challenge richer. Two: It’s okay to ask for help, and to follow-up if your first request for assistance fails. And three: experts and professionals, especially certified and credentialed, can, in the long run, save you time and money, especially when tactically deployed on your hardest problems.

Stafford County Order Book 1689-93, page 319; Stafford County Microfilm, reel 7, image 217 (Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia)

Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Vic Dunn, professional genealogist extraordinaire, for the blessing of sharing this citation, the abstract screenshot, and the link to the online microfilm images of the original manuscript order book.

3 thoughts on “1692 Order Freeing Abraham Little (1671-1720), Indentured Servant, My Surname Immigrant Ancestor”